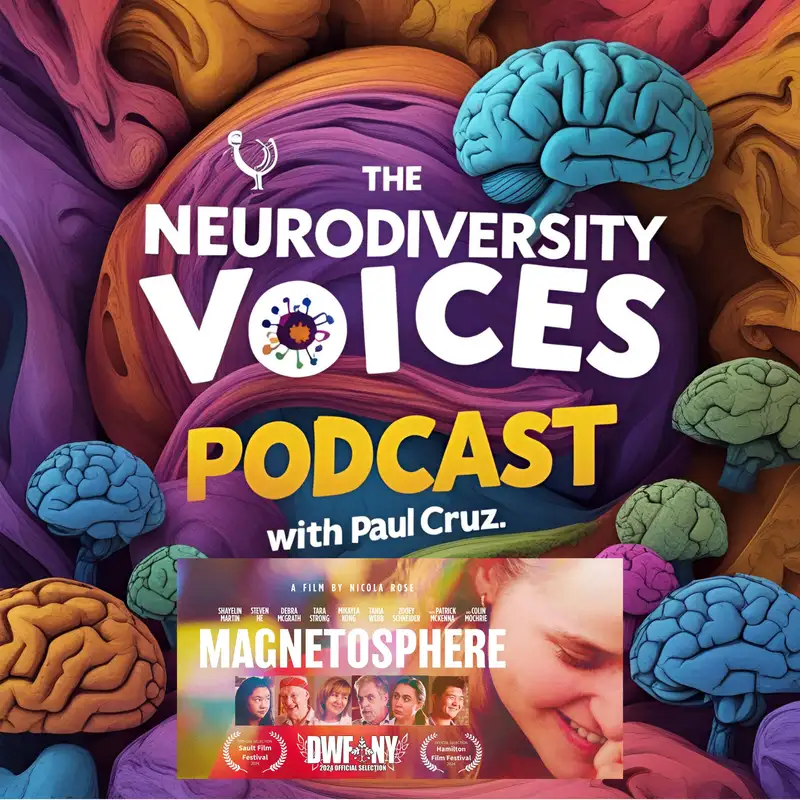

Exploring Synesthesia Through Film with Nicola Rose

Download MP3Welcome to the Neurodiversity Voices podcast. I'm your host Paul Cruz, and I'm thrilled to have you join us on this journey of exploration, advocacy, and celebration of neurodiversity.

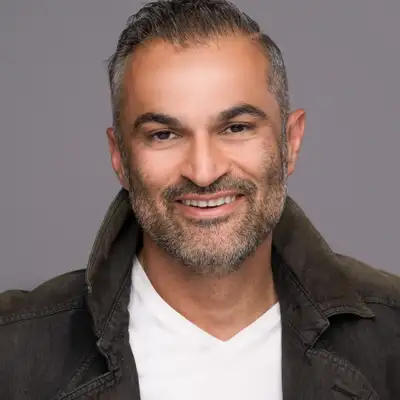

Gino Akbari:I'm Gino Akbari, your co host. Together, we'll have meaningful conversations, share inspiring stories and challenge misconceptions about neurodiversity.

Gino Akbari:This podcast is for everyone. Whether you're neurodivergent yourself, an educator, a parent, or just someone curious to learn more. Our goal is to amplify voices, foster understanding, and spark change in the way we view and support neurodiversity. We are

Gino Akbari:so excited to have you with us as we celebrate the beauty of diverse minds and work toward a more inclusive future.

Gino Akbari:So sit back, relax and let's get started. Welcome get We're speaking with filmmaker, Nicola Rose. She's the writer and director of Magnetosphere, a coming of age film that follows 13 year old Maggie as she navigates her first love and a big move and discovers that she experienced the world through synesthesia.

Gino Akbari:It is heartfelt, funny, and visually stunning. Nicola, welcome to the show.

Nicola Rose:Thank you so much, and thanks for the kind words.

Gino Akbari:Let's start with what drew you in. What made you want to tell a story about a young girl with synesthesia?

Nicola Rose:Know, synesthesia was something I heard about years ago. I think originally, I was trying to remember where originally because a lot of people have been asking me this question and I think it was on the radio. I think I was in the car with my mom. I think I was in my teens. I think I was listening to the radio and they were talking to people with synesthesia on a program.

Nicola Rose:I'm from The States, so this was NPR and they were talking about, you know, people with synesthesia are called synesthetes and they were talking to people who could like hear color or experience sound as texture, like physical texture and things like that. And I found it really fascinating, but then I didn't think about it again for years and years and years. I just had it like way back there in the recesses of my mind. It was in storage. It was way, way back there.

Nicola Rose:And I forgot about it for many years until I had done at that point, I wasn't even making films. As a teenager, that wasn't really my goal yet. That wasn't really That came later. So years later, had done a bunch of short films. I had done one feature film, was Good Bye Petrushka, which was my starter feature film.

Nicola Rose:I always say it was my film school because it taught me how to make a feature film and it, you know, it allowed me to make mistakes without the stakes being too, too high. And it taught me a lot of what to do and some of what not to do and so forth. And after Goodbye, Petrushka, you know, I was thinking, So I definitely wanna do more movies, but what do I want to do next? And I had vaguely in mind that I wanted to do a story about a child or a teenager with either an extraordinary ability or at least, I shouldn't say at least, but either an extraordinary ability or like an extraordinary difference of some sort. And synesthesia came to mind after I saw another gorgeous film called Confetti, which is by the director, Anne, who eventually it is gonna get back to Anne that I have mentioned her name like 50 times in the past few days on all these podcasts because she did a beautiful film.

Nicola Rose:It's a Chinese American film called Confetti. It has to do with a little girl who has dyslexia. And, you know, it's it's this very quiet, very independent, very small film. I loved it. I loved the way that the cinematography was done such that there were all these, like, POV shots showing us kind of the interior of the little girl's mind.

Nicola Rose:Like we would be outside her mind, we would be looking at her from without and then all of a sudden we'd be looking from within outside like we'd be we'd be her all of a sudden we'd be looking at stuff from her point of view. And we would see like, if she was trying to read letters, Chinese characters on a blackboard, we would like see them like twist and turn from her point of view in midair. And we would see how they were changing and we would be like, oh, oh my gosh, we're looking at stuff from her point of view. And it was so cool. There's no way that this was the first film to do this, but I happened to see it at a moment when I was trying to figure out where did I want to go next.

Nicola Rose:Synesthesia, it doesn't have a lot to do with dyslexia, but it is very generally speaking of the same family of neurodivergences. And so I was, I was having a conversation with my now ex and saying, would love to do a story like that about, you know, maybe a kid who has like, I don't know this through that or this or listing things. And he said, well, what about synesthesia? Because you've mentioned that before. And I was like, yes, synesthesia.

Nicola Rose:And, you know, it's such an obvious like, when you think about it, I don't know how much you guys you are the neurodiversity voices. You may know more about synesthesia than I do, but like, it's not just auditory and visual, but there is so much of it that is auditory and visual. Like so often it is that it seems like a really super obvious thing to put on TV or to put on film. And in fact, after looking it up, I was like, oh my gosh, why have not more people done this? So this challenge that I set myself was how do I depict synesthesia on screen such that people can understand what it is even if they've never heard of it, never heard it before.

Nicola Rose:And also how do I do it on a limited budget? Because shockingly, I had a limited budget. That was that was the challenge I set myself was how to depict this so that even if synesthesia was nothing you had ever heard of, you could still kind of learn along with the character and discover alongside her what was going on with her brain.

Gino Akbari:And once you knew that this was your focus, how did you balance portraying synesthesia in a way that feels authentic to people who live with it while still making it cinematic and relatable for those who've ever experienced it?

Nicola Rose:Man, you guys asked the right questions. I was just talking to somebody about this because like, authentic is the word, isn't it? It's such an important distinction because it can't be right. There is no right. There's no accurate, right?

Nicola Rose:Because no two synesthetes, or for that matter, no two neurodivergent people experience things the same way. Like probably no two neurotypical people experience things the same way. Like my notion of purple is probably not the same as your notion of purple or whatever. You know, we're never going to know because we can't describe qualia in those ways. Anyway, long story super short, because this used to obsess me as a kid, I would be like, Oh my gosh, what if my mom doesn't see red the same way I see red?

Nicola Rose:What if she sees this strawberry as yellow? The way what I think is yellow, but she thinks it's red. And, my God, it blows my mind. And, you know, I think I had a lot of time on my hands as a child. But point being, you know, the best that you could only thing that you can do is make it be authentic, and the way to do that is to go to primary sources, and the way I did that was to go to Facebook, and there is at least one, There's probably more.

Nicola Rose:There's at least one huge Facebook group out there, which I think is just called synesthesia. And it's like synesthetes, hundreds, maybe thousands from I think it's thousands from all over the world who experience, you know, all different kinds of synesthesia, hundreds and hundreds of different kinds of modalities. And, you know, I put my innocent little post in there saying like, hey. I'm working on a movie, and I would kinda like to talk to some people and find out what you experience. And, I mean, I don't know what I expected.

Nicola Rose:I got deluged, naturally. Everybody wanted to tell me their experiences. And so next thing I knew, I yeah. Yeah. You know, I couldn't speak to everybody who wanted to speak to me.

Nicola Rose:I think I ended up speaking to about 70 different people. Like, it was a lot. It was way too many to ever use all their experiences in the film. You can't. You know, you would just it would be an overload.

Nicola Rose:So I think I winnowed it down to like five people ultimately whose experiences kinda hewed most closely to what Maggie, who is the main character in the movie, what her experiences were gonna be. So everything that you see in the movie, which is streaming now across Canada and across The US and across Mexico on kinda all the major streaming platforms, Amazon Prime and Apple TV, if you see this movie, you can look at any experience that this child has of synesthesia and know that experience was told to me by somebody who had that actual experience. Nothing is 100% made up. There may be modifications and like things that are massaged slightly to like work on screen. Because sometimes you don't have all the information, so you have to fill in the gaps a little bit, if this makes sense.

Nicola Rose:But there's nothing in you can't just make stuff up. That's that's how you be you ask, how do you be authentic? The way to be authentic is ask people, okay, what did you experience? Now I'm gonna write this down. Now I'm gonna test it out on audiences and see, is this working for you?

Nicola Rose:And if people are if it's resonating with people, then you know you're doing your job. And it can never be fully like, you're never gonna resonate with a 100% of people. Like, there's a super quick example that I always give is there's a scene in the movie where Maggie's synesthesia, which is not always a pleasant thing because synesthesia isn't always a pleasant thing, where it makes her nauseous and she throws up because she's overstimulated and all the things that lead to that. One of my neurodiversity consultants that was working on the film with me and she has synesthesia and knows a ton about the topic. And she looked at that and said, you know, that scene did not work for me at all.

Nicola Rose:I don't know what was going on. Whereas the other person or not sorry. Not the other person who was also a synesthete and also a neurodiversity consultant and also had worked on the film with me was like, Oh my God, something like that happened to me when I was a kid. And it was this loud sound and it gave me a migraine and made me throw up. So, you know, you're never going to resonate with everybody because, like, you can't, but the best that you can do is do your do your due diligence in trying to be as authentic as possible and resonate.

Nicola Rose:I don't wanna say with as many people as possible, but as strongly as possible with the people that you are trying to resonate with, which in this case is neurodivergent people and the people who love them, people who wanna understand them, people who wanna say, okay. I don't really get what's going on with my daughter, but I know she experiences stuff differently. So what is she experiencing?

Gino Akbari:The film takes us back to 1997 with the Hale-Bopp comet in the sky. Why did you choose that moment in time as the backdrop for Maggie's story?

Nicola Rose:97 1996 and 1997 were the two years that the Hale Bopp comet was passing by Earth, and I used that as a sort of anchor event to sort of bookend the story. There's a lot of reference to outer space and spatial phenomena. One of the characters is an astronomy student. Maggie has a doll that she talks to, you know, when nobody is looking, who is like a little space Barbie. So outer space is sort of a constant background character in this film or or like a background presence, whatever you wanna call it.

Nicola Rose:But, you know, I also I was very keen to take it back to a time when the characters wouldn't, like, constantly have devices in their hands. And, you know, there's so much in this story that would have been less interesting or less impactful or would have been resolved so much more easily if somebody could have just Snapchatted somebody else or if somebody could have just, like, looked it up and googled, what am I experiencing? Oh, synesthesia. Okay. Okay.

Nicola Rose:Done. You know? It's like a five minute movie. It's a lot easier it's a lot easier to let the story be a story that takes place in its own at its own pace if everything is not so easily at the character's fingertips. And I think, you know, which is not to say that no stories should be set in the present day.

Nicola Rose:I think some stories work way better in the present day. My first feature was set in roughly the present day that worked well for that one. For this one, there was just something about it that I wanted to feel a little more like a memory and a little more like something that didn't necessarily quite just happened last week, but happened more like when you were a kid. It's it's not really a kid's film, but I want it to harken back to like when when we were kids, when whoever's seeing it might look at it and say, oh, yeah, that feels like something. Even if I didn't experience that, it feels like something I experienced.

Nicola Rose:I I go back to something that Greta Gerwig said about Lady Bird, which is set in roughly the same it's like six years later. And she used a certain grain of film because she wanted it to feel like a memory that took place in the early two thousands, like when she was in high school. And it did feel like that time, like she's a couple years older than I am. So I felt like she got it aesthetically right somehow in a way that's hard to quantify. But she, you know, she wanted it to look and feel like a memory.

Nicola Rose:And that's what I was going for here. Now we shot on digital, so not with Grain, but with things like characters using Walkman and listening to audio cassettes and writing things out longhand and, you know, not being glued to iPads and stuff like that.

Gino Akbari:Nostalgia. I think for me, it was magical.

Nicola Rose:Thank you.

Gino Akbari:Yes. I just thought the whole reference to the comet and the flame and the color has add, I thought it married very well because I thought it was actually magical. That is what attracted to me. I'm not neurodivergent. I'm just almost an outsider here.

Gino Akbari:So for me to watch that, learn about it, and full disclosure, I did not know what it was. Cool.

Nicola Rose:It is because really interesting. Okay.

Gino Akbari:Yeah. It was because of this interview, this that I had an opportunity to learn about it, watch it, But I thought that was brilliant because it made it so magical, the happy moments. Was

Nicola Rose:That's actually so good for me to know because here's this person, you, who didn't know what synesthesia was, who wasn't part of that community, and it made sense to you. So that's heartening for me. It's like, oh, okay, this makes sense, even to somebody who's not already initiated.

Gino Akbari:No. I thought it was personally, as an outsider in this case, brilliant because it was almost like a beautiful mind. I did not take anything negative from it. I took everything positive and there was a sort of this magical touch to it where I'm in awe and I'm like, wow, she can see these colors. We can't, I can't.

Gino Akbari:So that came across

Gino Akbari:very

Gino Akbari:nicely. So,

Nicola Rose:yeah. That means a lot to me to know that it makes sense to somebody who doesn't experience it. And I have a lot more I could say about that, but basically, you.

Gino Akbari:Yeah. No worries. So so Maggie's character feels layered and real. How did you develop her emotional arc? Which parts of her are drawn from your own life, if any?

Nicola Rose:You know, very little, actually. I was thinking about that because a lot of people assume that the character is based on me, and that's a natural assumption. I'm actually if anything, as a child, I was probably a lot more like her little sister. I was very loud, very musical, very probably a little obnoxious, probably a lot obnoxious. You know, Maggie is more shy and cautious and trepidatious and doesn't, you know, she keeps her cards close to her chest and doesn't necessarily want people to know what's going on with her unless she trusts them fully.

Nicola Rose:If anything, she's a little more like my sister and her sister is a little more like me, which is interesting. But, you know, the emotional arc of that character came almost entire I mean, what's on the page is what's on the page, which is the words you see on the screen and a certain amount of screen direction saying, like, she says this flatly or she says this trepidatiously or whatever, but not too much. But so much of the pretty much a 100% of the character's emotional particularity came from Shailen Martin, who is this brilliant, intuitive, canny 17 year old actress who actually just 15 when she played Maggie, who basically just like colored in the lines herself. Like, everything up there. Like, yes, I directed her.

Nicola Rose:Yes. I said, okay, let's go this direction with this, and let's try less of that and more of this and whatnot. But basically, she's so intuitive and so almost just like just sort of like a baby animal, just all these raw instincts she has about what to do that you don't really want to mess with anything she does. You kind of you know, I felt as though I was there to shape and guide occasionally, like, say, okay, let's pull back here or let's do more of this there. But, basically, just let her be let her be what she was.

Nicola Rose:She was cast for a reason. They say 98% of directing is casting, and that's that's pretty true. And I would say it's pretty much all her, and I'm just there to supervise.

Gino Akbari:The film shifts between muted tones and bursts of vivid color and music. How did you and your team work together to capture Maggie's sensory world visually and sonically?

Nicola Rose:There were a lot of meetings, you know, before we ever got to set. There were we were in preproduction for well over a year, which is actually a pretty expedited process, you know, for people who are familiar with indie filmmaking. Even for an independent low budget film, that's still pretty quick. And, you know, there were several different departments that had to sort of coordinate and get together in terms of making all of those, whether it was the visual stuff, whether it was the auditory stuff, whether it was the post production visuals, or whether it was the composition, making all those things flow together as one sort of one sort of piece. All of all of them had to coordinate and so much happens in preproduction, so much planning.

Nicola Rose:And then when you get to set, so much of that actually comes apart and it turns out, oh no, you know what? That actually isn't going to happen the way we thought it was going to happen. So you have to be prepared to roll with punches and find out that, okay, no, this, for example, some color lighting that you thought you were going to get or some angle that you thought you were going to get, some camera angle you thought you were going to get is not going to be possible or some, some kind of lensing is not going to be doable. I don't know. So you end up modifying on the fly any number of things that end up, like in the end coming out different and who knows, perhaps better than what you expected in the first place.

Nicola Rose:And then a great deal also happened in post production with the anything that you see that looks like animation, anything that's, you know, swirls coming out of her head and, you know, her drawing stuff in the sky with her finger and stuff like that, all of that was designed ahead of time and then made to come to life by a visual effects team led by a supervisor whom I worked with one on one, and then he worked with the rest of the team and communicated the workflow. And so all of that is to say that so many hands were involved in this, and it all had to there are just so many pieces of the puzzle that had to come together to make it one coherent whole.

Gino Akbari:At the heart of that world are Maggie's relationships. Her first crush on Travis and her deepening friendship with Wendy. How did you approach showing the contrast between those two connections, especially through a neurodivergent lens?

Nicola Rose:You know, to me, the most important thing was that nobody ever quite 100% understood what was going on of the three characters. Of the three of them, I would say Wendy is the most aware by far of what's happening. But even she, you know, I don't think it's a spoiler to say that here's this 12, 13 year old girl who's discovering that she might be queer or at the very least, she's got this crush on her female best friend. And this is something that she didn't expect. It comes at her out of nowhere.

Nicola Rose:And so she's dealing with her own set of worries and confusions and feelings that, like, if we told the story from her point of view, it would be a whole different movie, and it would be just as interesting, if not more interesting. It would be a whole other story. There's there's, like, there's endless other material there, I'm sure. And, you know, Maggie is sort of at the apex of the love triangle there with Wendy on one side, Travis on the other, and the two of them never meet. They never Wendy, obviously, she hears about Travis all the time way more than she ever wants to, but she never she never actually comes into contact with him.

Nicola Rose:So everything was shot very separately, and it did feel like two separate worlds.

Gino Akbari:There's also that quiet but powerful bond between Maggie and her art teacher. Why was that relationship so important in her journey toward self trust, and how does it speak to the experience of being understood without needing to explain yourself?

Nicola Rose:I think there had to be one adult there who wasn't a parent who looked at her and saw what was going on and understood without even necessarily being neurodivergent herself. We don't know that she is. We don't know that she isn't. I think she might be, but we don't you know, the question is never asked or answered. But I think it's really important that, you know, I think as adults that work with children, and I work with children in the sense of being a director who directs child actors, I have a responsibility to make sure that they feel safe and playful and able to create good work and as though as though they can do their best work on set.

Nicola Rose:And I think if I were an art teacher in an art classroom, I would feel that I had that same responsibility to always have an eye out to know what was going on to what's the word I'm looking for? I would want to try and be as aware as possible of what was going on inside these children's minds to try and support them through what is gonna be one of the most difficult transitional times in their lives. And so it was really important to me that that character of Miss Dearing being unusually empathetic. And her actress, Deb McGrath, who is herself enormously empathetic, said that the one thing she figured out right away about that character is that she really likes kids. Like, she likes them as human beings and she wants to know what's going on inside of them.

Nicola Rose:And I think she does have that sort of almost clairvoyance of knowing, oh, you know, this this kid may have a neurodivergence or this one may have a maybe a a crush on this one or this, you know, this one may be having trouble here or whatever. And I think, you know, we're not all lucky enough to come across that person. I wish we were, but we should all be so lucky. We should all be so lucky to have a miss during in our lives.

Gino Akbari:Right. When you look at Maggie's synesthesia, do you see it as a metaphor for the broader neurodivergent experience or for what it feels like to be slightly out of sync with others?

Nicola Rose:Yeah. I think it's even bigger than neurodivergence, actually. It's interesting you put it that way because I think it has to do with feeling slightly out of sync or seriously out of sync. It's not necessarily neurodivergence, although so often it does come down to that. But I know that as a child, I felt massively out of sync with people around me as soon as I was old enough to realize that there were differences between people.

Nicola Rose:Because, I mean, there's a certain part of childhood where you were too young and too silly and too happy to even, like, have a clue. But as soon as you do start becoming more aware of who's around you and that not everybody likes you and not everybody likes each other and so forth, you know, you do start at that point to feel as though to to feel uncomfortable. And I think, you know, synesthesia, it could have been just about anything. It could have been dyslexia. It could have been autism.

Nicola Rose:It could have been ADHD. It could have been some other difference that's maybe a physical difference that's not necessarily a neurodivergence. I mean, not that that isn't physical, but talking about a different kind of physicality here. I think anything that makes you feel out of sync with the world could have been the stand in here. And synesthesia just happened to be one that's unusually cinematic, so, of course, I had to go with it.

Gino Akbari:And in telling that story, what kinds of conversations about neurodiversity or emotional difference did you hope Magnetosphere would inspire?

Nicola Rose:You know, what I was hoping would happen, and it has happened so far a lot of times, is that people would discover by watching the film that they themselves either had synesthesia or had something similar and they had gone all this time, you know, maybe way into adulthood without ever realizing. I had a feeling that was going to happen. I didn't realize how often it was going to happen. It has happened just about every time the film has screened anywhere. There has not been a single time that somebody has not come up to me afterwards and said, Oh my gosh, you know, I experienced this.

Nicola Rose:I didn't realize what it was. And you know, maybe they had heard of it, maybe they hadn't, maybe they didn't realize all the different ways you could experience it. But yeah, there's just there's what I think is we we go around with our own mental landscape looking and feeling a certain way to ourselves. And we don't necessarily like question that because like, why would we? Why would we?

Nicola Rose:Why would we say, why do I think about orange when I think about this subject? Like, we wouldn't if we have thought about orange when we think about aerosol spray cans since we were six years old, why would we go around questioning that? We would just, it would just be a vague association in the back of our minds and we're not going to like think about it. But if somebody makes us think about it one day, then we're going to make the connection. But otherwise I think we take our mental landscape very much for granted.

Nicola Rose:And unless somebody actively, like a therapist or some something, somebody makes us actively question these things that we think about, we're not going to, like, suddenly take them out and examine them. So, yeah, hopefully a story like this makes us do that.

Gino Akbari:Now you've spoken about having neurodivergent traits yourself. How has your personal background, whether that's neurodivergence, your artistic journey, or both, shape the way you tell your stories or even direct?

Nicola Rose:You know, it's been evolving ever since I made my first feature film, Good Bye Petrushka, which was not supposed to be about neurodiversity, but I kept hearing from autistic viewers who had identified with the main character. And if you hear that a few times, think, okay, well, that's interesting. But I started hearing it enough that I thought something interesting is going on here. Although, as far as I know, from from having been tested, I, am not autistic personally. I do have some other neurodivergences.

Nicola Rose:I apparently have ADHD from testing, and I I did discover that I had synesthesia as a child, although I don't have it anymore. So that was something that I discovered along the course of doing the research for this movie. So that was perhaps one of the more interesting personal discoveries that I made, you know, making this movie because here I am thinking, I'm making this movie that's, like, a complete fiction. This has nothing to do with me. I just made up a story.

Nicola Rose:And it's like, no surprise. The more you think you're writing fiction, the more you're actually writing by yourself. It's it's like it's always that way.

Gino Akbari:On the production side, what was your favorite scene to direct, and why did it stand out for you?

Nicola Rose:My favorite scene to direct. There are a few that I can't say without giving away spoilers. So just thinking my way through it here. I think one of my very favorite scenes to direct was an early one where, it's it's early in the story where Maggie asks her father. She asks him a question.

Nicola Rose:She says, why am I ugly? And he responds in a very unexpected way. And it goes in a direction that ends up it ends up bringing back like a sort of motif that comes back a few more times for the for the rest of the story. It will it will sort of come back to her every time she looks in the mirror, which her looking in the mirror is also a motif in the story and her being unable to come to to quite come to peace with what's in her reflection. And that was such an interesting that was such an interesting scene for me to direct because I didn't expect any of the ways that the actors were going to play off of each other.

Nicola Rose:And so the ways that Patrick McKenna playing Russell, the dad, and Shayelin Martin playing Maggie dealt with each other and bounced off of each other in that felt so real to me and felt so authentic and interesting that I felt as though I could have watched that scene play out for days and it could have still been interesting. It was I I knew where it was going. I had written it, and I was still surprised by where it went, which is just a testament to how how well they do what they do and how much nuance there is to how they play their characters.

Gino Akbari:Getting an independent film like this made is no small task, of course. Did you face challenges convincing others of the importance of a positive coming of age story for a new diverse audience?

Nicola Rose:I don't think it was necessarily difficult to convince people of that. I think what's difficult to convince people of in general is that independent films should be made at all because, you know, they are not, let us say, known for making large amounts of money. There is no money for them unless you well, it depends on what country you're in. There are some countries. Canada cares about them a little more than The US does, and France cares about them very much.

Nicola Rose:You know, it's all relative, you know, because people in Canada will say, oh, it sucks to make independent films in Canada. Nobody cares. Think, yeah, but in The U. S, you have to ask your friends for money. There's there's, there's no agency at any level of government in the state and the city.

Nicola Rose:Cares. Nobody cares. Nobody wants you to make anything artistic ever. Now I am oversimplifying this grossly, but I also don't think I'm oversimplifying it too much. It really depends where you are, and it really depends what you're trying to do.

Nicola Rose:I think what is difficult once you've actually gotten past the hurdle. Let's say that people have given you money or have invested money and they know that it may not come back, but they're hopeful that it will. And they've they've given you a certain amount of funds to make your film. I think I've run into a surprising barrier with convincing people that stories about a young child are important and that stories about girls are important. As I've had it put to me a couple times, you chose the wrong sex and you chose the wrong age.

Nicola Rose:And that's something that I find disgusting. And I find that attitude disgusting. I don't understand how anybody can wholesale look at one whole sex or one whole group of age and say, these stories are worthless. I understand that we're dealing with we're dealing with a movie economy where Disney and Marvel rule the day and there is nothing else. But it's wrong because it excludes all other points of view.

Nicola Rose:It's almost exclusively just superhero movies, retreads, and sequels at this point. And what that does is it shuts out 99.99999% of other stories that might be told. And are they all going to be good? No. Are they all going to be worthy of being told?

Nicola Rose:No. Am I even saying that this one is? Not necessarily, but I would hope that it is because I would hope that it would resonate with people who have felt weird and who have felt different and who want to see neurodiversity represented on screen.

Gino Akbari:And once you were on set, how did you create an environment where the emotional honesty of the story could really shine?

Nicola Rose:You know, the best thing that you can do as a director is stay as calm as possible all the time, which is difficult because you are always on the clock, and you always have point zero zero zero one five seconds to complete everything. But if at all possible, if you can keep that information hidden from your actors so that they feel calm, so that they feel playful, so that they're able psychologically to do their best work, you will get the best results. And so it's that your job is to make them feel as relaxed and as comfortable as possible and as though they're not at work at all and as though they have all the time in the world. And they absolutely do not, but you want to give them impression that they do. But, yeah, if you are stressed and if you are showing your stress, and we're all guilty of it.

Nicola Rose:I've been guilty of it. Every director is guilty of it. I think if if if you show your stress, you know, the actors are going to also be stressed, and their stress is going to be what kills the scene, unfortunately. So you owe it to you owe it to everybody not to not to let that be known.

Gino Akbari:So since the film's release, what kind of feedback have you received from audiences and especially from people with synesthesia? Has any response stayed with you?

Nicola Rose:Yeah. You know, when you do something like this, I think when you create anything, you even though, yes, there might be people around you, you might have a team around you, and obviously, this this sort of thing takes a huge team, you are in a sense doing it in a vacuum because you're not hearing the wider world's reaction to it. You're only hearing if you're hearing any reaction to it at all, it's from a small group of people that you're working with. So you don't really have a very clear idea of what you've made. If anything, you have a very distorted idea of what you've made.

Nicola Rose:You have no clue what you've made. So I was very gratified, very shocked to receive some of the most beautiful critical reviews I have ever seen. I thought, you know, I didn't think, but I usually don't actually, but you know, if anything, I, I, I was expecting to, I was expecting to hear, you know, this is kind of weird. I don't know. It's an indie, it's low budget.

Nicola Rose:Like it tries. I'm not really sure what it is, whatever. I don't know. I just figured it would be something in the middle of the road. The critical reception.

Nicola Rose:First of all, it is very hard for independent films. And I mean truly independent films here. I'm not talking a $2,415,000,000 dollar, 25,000,000, $35,000,000 budget indie films with an actual studio that are not independent. I'm talking about truly indie films that are made for sub $1,000,000 that are made for sub $500,000 that are made for nothing. It is so hard to get them reviewed at all.

Nicola Rose:We have had 16 critical raves. And yes, the publications are small because publications like The New Yorker, publications like The Hollywood Reporter, publications like Variety, publications like The LA Times, they do not look at these things except in the rarest and weirdest of circumstances. And by the way, that's wrong because small voices will never be amplified. As long as that continues, it is absolutely dead wrong. They owe it to everybody to look at small work, but I'm not going to change that.

Nicola Rose:So I'm just saying it. Nobody's hearing me. It's fine. Whatever. You guys heard me.

Nicola Rose:If nothing else, the point is the people who are willing to look at it, I think they're doing heroic work because even if they say it sucks, even if they say this is the worst thing I have ever seen, they're amplifying small work and there is no way other than word-of-mouth for small work to be known about. They're doing something incredibly important, even if they pan the work. So the fact that I don't know how many reviews we've had now. I think it's 16. I don't know.

Nicola Rose:That's for a tiny indie film. That's a big number. I mean, it's not because you look at, you know, you look at a big major release, big major studio release that has 350 reviews, 250 reviews, something like this. You know, you're lucky if you get 10. We have 16.

Nicola Rose:They are all like. They're so positive that they read as if I paid off the critics to write them. I can assure you I did not because my net worth is about $10, but it is has just been a gift, and I have been so grateful. I cannot even tell you. I did not expect that.

Nicola Rose:I don't know what I did expect. I wasn't expecting, like, something horrible, but I was not expecting this.

Gino Akbari:Looking back, what did making magnetosphere teach you that will influence your future projects?

Nicola Rose:Be kind to people. That's it may sound like a little bit of an enigmatic remark, but each project in its own way reminds me whether by positive or by negative reinforcement that being good to people is the only way to do your work well because there is just absolutely no excuse ever to be any other way. And that you can make or break somebody's experience. You can make or break somebody's life by being a force for good or a force for bad in their world during an experience where they're vulnerable, where they're acting, where they're directing, where they're doing something. You owe it to everybody around you to be a good person.

Gino Akbari:And finally, if a young neurodivergent girl is listening right now, dreaming of telling her own stories, what advice would you give her?

Nicola Rose:This is gonna be a surprising one. I would say cultivate other interests besides the arts. I'm not saying don't write it down. I'm not saying don't make a movie. I'm not saying don't write a story.

Nicola Rose:In fact, I am explicitly saying do those things. Do write it down, whether it's a movie, whether if it's a book, whether it's a graphic novel and you like to draw. I don't know. Do it. Write it down.

Nicola Rose:Make it. But also make sure that you diversify and spread out your interests among other things. Make sure that you are interested also in a physical activity. Make sure that you're interested also in a science. Make sure that your interests go beyond the arts because limiting yourself to this one thing is not necessarily healthy.

Nicola Rose:And I have found that out the hard way. And as an adult, I'm still working on learning to diversify my interests.

Gino Akbari:That is great advice for anyone, and I would just like to add something here before we wrap up. You said a few times during this interview that the movie was made for people with neurodiversity. I'm going to say that from my point of view, I think the movie was made for everybody else other than them because I know what it is now. I never knew that. And I think movies like this are meant to move and inspire and bring to our knowledge about topics like that where we didn't know.

Gino Akbari:I had zero clue what synesthesia is or the word existed. I knew autism and ADHD but I did not know that this existed. Now I know and my wife will be watching it and my 14 year old daughter will be watching it. Yeah, the message and I mean that because the message is for everybody else. Now I can walk around and when somebody says that, know exactly what you mean and what it is.

Gino Akbari:So thank you for delivering that message to people like me as well.

Nicola Rose:Thank you. I mean, oh my gosh, you know, I didn't set out to make an issue film or deliver a message. I really never do, but I think if work is good or for that matter, if work is bad, sometimes people take their own messages from it. It's really not a comment necessarily on the quality of the work so much as it's a comment on the multi multi multi functionality. It's the word I'm looking for.

Nicola Rose:I think what I'm saying is a thousand people will see the same film a thousand different ways, and it can have a thousand different effects on them and inspire them to do stuff that might have no logic to it, but for whatever reason, you know, when I look back at some of the things that inspired Magneto Sphere or Good bye Petrushka for that matter, because I keep forgetting I made this other feature film, like, few years ago that apparently was about an autistic girl, although I didn't, like, mean to do that. Hey. So that's what happened. When I when I think of some of the things that inspired that, gosh, especially with Goodbye Petrushka, they have no logical connection to what actually came ultimately the result of which is so so far away from anything that might have launched the idea. You end up on a very, very different route is what I'm saying.

Gino Akbari:Nicola, thank you for joining us.

Nicola Rose:Thank you, guys.

Gino Akbari:If you enjoyed this conversation, please rate, share, follow, subscribe, and leave a review on your favorite podcast app.

Gino Akbari:If you have any questions, ideas, or stories you'd like to share, please feel free to contact us. Our website is neurodiversityvoices.com. Please fill out our listener survey form. We'd love to hear from you.

Gino Akbari:Until next time, take care, stay curious, and keep celebrating the beauty of diverse minds.

Gino Akbari:Thanks for listening to the Neurodiversity Voices podcast.

Creators and Guests